I don’t think one can say this too many times. Margins are important, perhaps the most important part of a work. They are the frame within the frame; a place for the eye to rest while soaking up the artwork or letters contained within.

I don’t think one can say this too many times. Margins are important, perhaps the most important part of a work. They are the frame within the frame; a place for the eye to rest while soaking up the artwork or letters contained within.

So why do so many contemporary calligraphers and book artists neglect these wondrous white (or background) spaces?

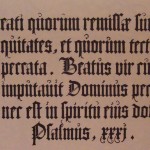

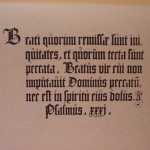

Here are two photos of same blackletter page. One has had the margins cropped off. The original has breathing room. It allows you to appreciate the texture of the lettering, to notice the darks and lights of the majuscules and to focus on whole words and sentences. The other should, even if you’ve never studied layout and design, make you slightly claustrophobic.

Here are two photos of same blackletter page. One has had the margins cropped off. The original has breathing room. It allows you to appreciate the texture of the lettering, to notice the darks and lights of the majuscules and to focus on whole words and sentences. The other should, even if you’ve never studied layout and design, make you slightly claustrophobic.

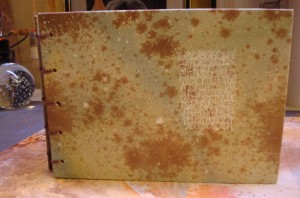

Manuscript page design has changed little since the first books were written. Whether you’re looking at a page from the Book of Kells or browsing the Saint Johns Bible Website, you will see margins that enhance the readability and artistic design of the page. Two very fine resources for studying traditional margins are The Calligraphers Handbook, edited by Heather Child (the paperback with the blue cover) and Edward Johnston’s Writing and Illuminating and Lettering.

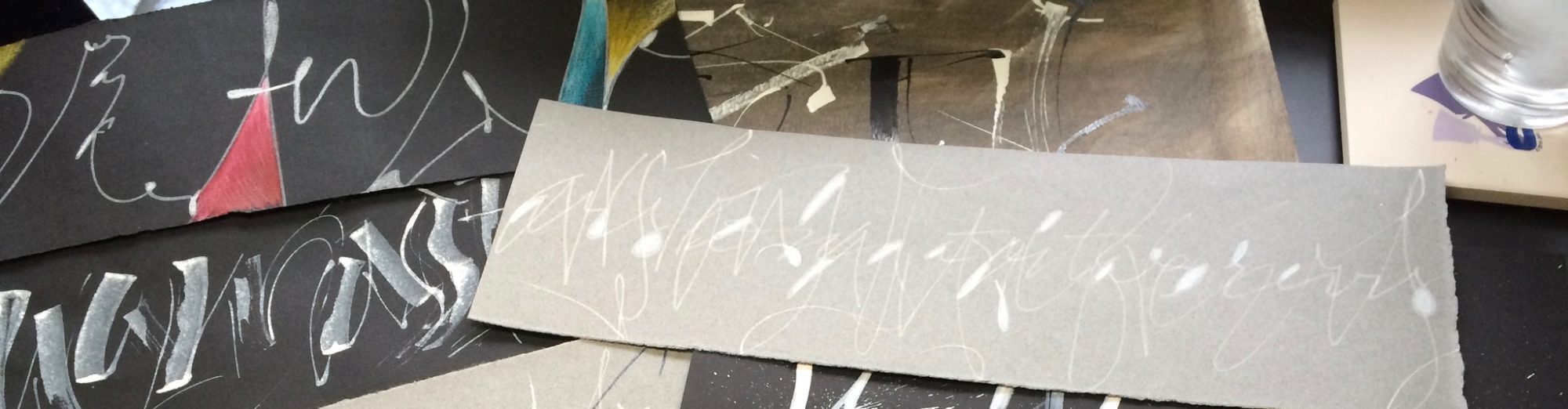

But what if you’re not designing a page in a book? What about contemporary art, addressing envelopes, or making a broadside? Space still matters.

But what if you’re not designing a page in a book? What about contemporary art, addressing envelopes, or making a broadside? Space still matters.

For more contemporary studies, Sheila Water’s Foundations of Calligraphy and Annie Cicale’s The Art & Craft of Hand Lettering both contain chapters devoted to layout and design.

Studying good calligraphic art is also a very good way to educate your eye. But as you dissect and study letter forms, don’t forget to look for what isn’t there, those magical places above, below, around and between. Margins, interlinear space, anywhere the lettering is NOT is equally as important as the finest letters you can create.